Tearing down highways is long and difficult work, particularly in a city with a culture that is so wedded to the automobile. Consider this: it has been five years since the Texas Department of Transportation released the CityMAP study, which analyzed the implications and logistics around tearing down Interstate 345, that little strip of connective concrete that cuts off Deep Ellum from downtown. D Magazine devoted an issue of the magazine to the I-345 removal idea way back in 2014. And can you believe it has been nearly eight years since urban planner Patrick Kennedy proposed the then-radical concept in a column in D? Since then, highway removal efforts have gone mainstream. The country’s new transportation secretary is even using them as policy talking points.

Enter a new study that attempts to kick Dallas’ highway removal project into a new gear. It refines some of the plans outlined in CityMAP. This 90-plus page report is being called the I-345/45 Framework Plan (admittedly not as catchy a title as CityMAP), and it was developed by the Toole Design Group, LLC, an engineering and urban design firm that helped plan the I-375 highway removal in Detroit. It attracted an extensive list of partner organizations and individuals and produced the report following a substantial amount of public input. This plan refines the CityMAP study in three key ways:

- It provides a more holistic view of the reasons for removing I-345.

- It dives more deeply into how such a removal would affect mobility, including a fascinating analysis of how a reconstituted street grid could handle traffic.

- It offers a land use vision for how to maximize the potential benefits of the highway removal.

Now, full disclosure: the report is also dedicated to the memory of the late Wick Allison, the founder of D Magazine, who had been a champion of the I-345 project since Kennedy first raised the possibility in our pages. The Coalition for a New Dallas, an organization co-founded by Wick, is also a driving force behind the completion of the “Framework Plan,” and tomorrow the Coalition is hosting an online symposium that will both present this new plan and outline its policy priorities heading into this May’s city council elections.

The timing of the report’s release is significant for another reason. There is a lot of transportation planning happening in and around downtown Dallas right now, and top city and regional planning officials want to plan all three major downtown projects—Dallas Area Rapid Transit’s D2 downtown subway connection, the I-30 canyon rebuild, and I-345—in tandem. At a recent council briefing, Michael Morris, the transportation director of the North Central Texas Council of Governments, said that TxDOT expects to complete a I-345 traffic study sometime soon.

The Toole study—which I will refer to as the Framework Plan for the rest of this piece—offers an important counterpoint to that TxDOT study. It provides broader vision and technical comparisons to help check whatever TxDOT’s assumptions turn out to be.

Let’s dive into some of the details:

Two Highway Removal Options

Unlike CityMAP, the Framework Plan doesn’t bother studying the option of keeping the elevated highway as is. Instead, it proposes two options:

- Transform I-345 into a surface boulevard and improve the existing street network to mitigate any traffic impact from the highway removal by shifting that capacity to surface streets

- Rebuilding I-345 as a “depressed highway,” but one within a narrower trench than laid out in CityMAP to mitigate the highway’s impact on the adjacent street grid

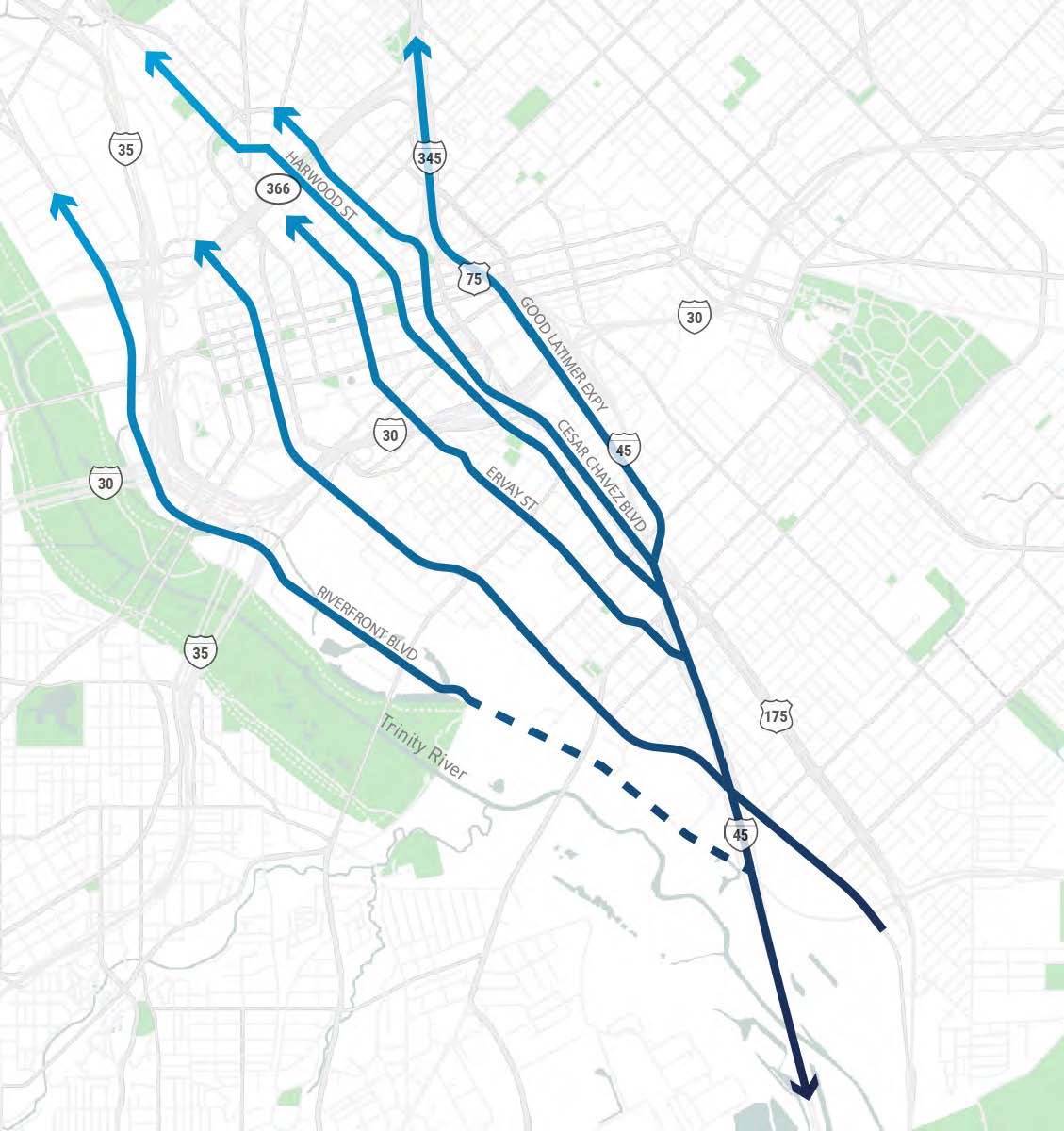

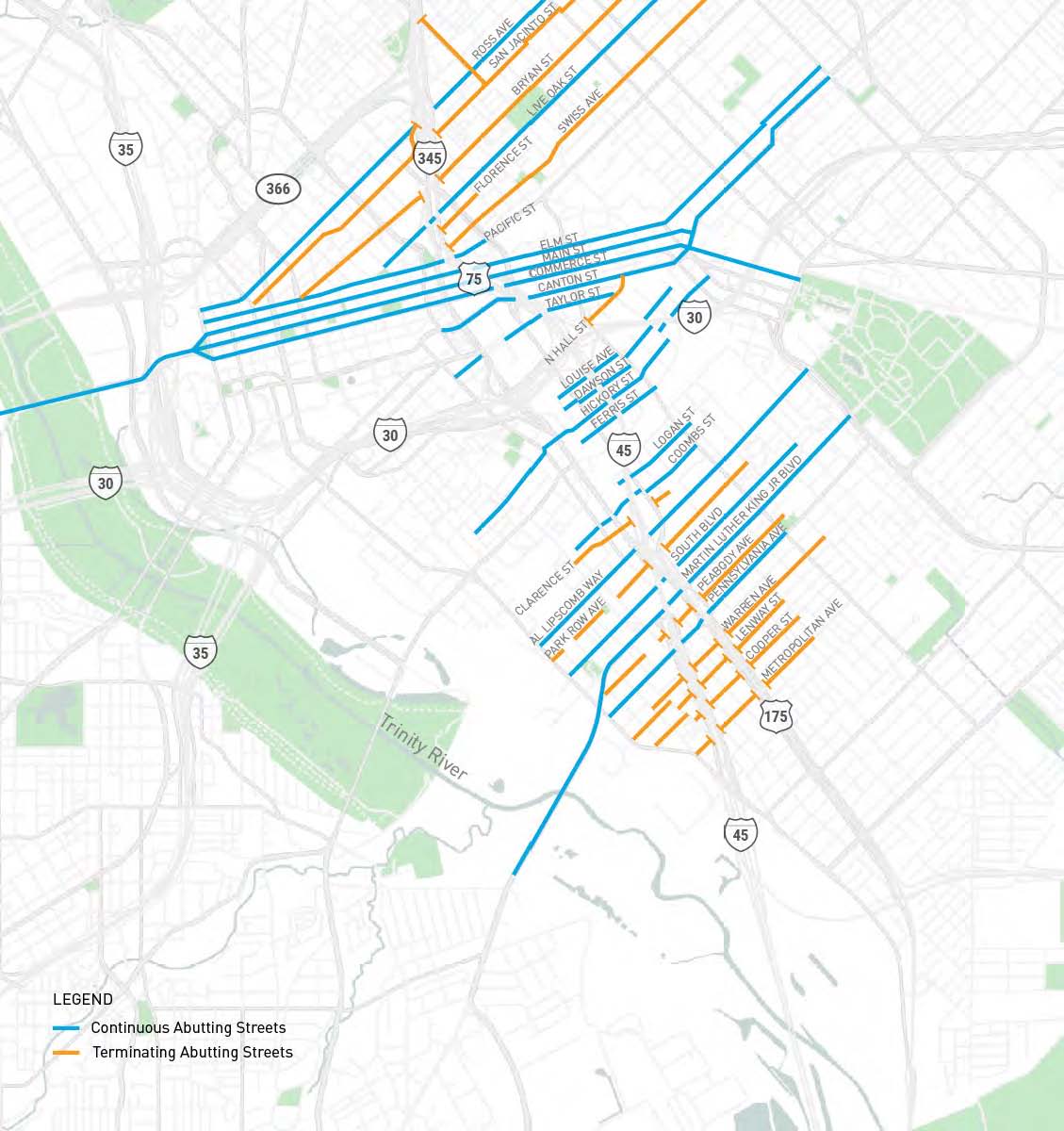

The study presents renderings that show what a reconstituted street network could look like. It maps how roads like Riverfront Blvd. and Lamar St./ Botham Jean Blvd. could create new connections from southern to northern Dallas that would alleviate the need to funnel all the existing traffic through the I-345 corridor.

Unlike CityMAP, the plan notably ignores maintaining I-345 as an elevated highway and reimagines the design of the so-called “trench,” or burial, option. This new plan instead proposes a shallower highway trench than the one proposed in CityMAP. It also creates additional street connections to divert highway traffic onto surface streets to reduce the required carrying capacity of a below-grade I-345. This would allow for a narrower barrier between downtown and Deep Ellum that could be spanned by bridges that restore a street grid that is friendly to pedestrians.

But if neither of these proposals provide for the same traffic capacity supplied by the existing elevated highway, where will all the traffic go? This is of particular concern to southern Dallas residents who use I-345 to commute to jobs north of downtown. Even if highway removal creates opportunities for the creation of future jobs closer to downtown at some point in the future, that hardly helps someone who needs to get to work tomorrow.

The answer to that question is the most fascinating and significant aspect of this new report.

Reimagining Mobility and Traffic Capacity

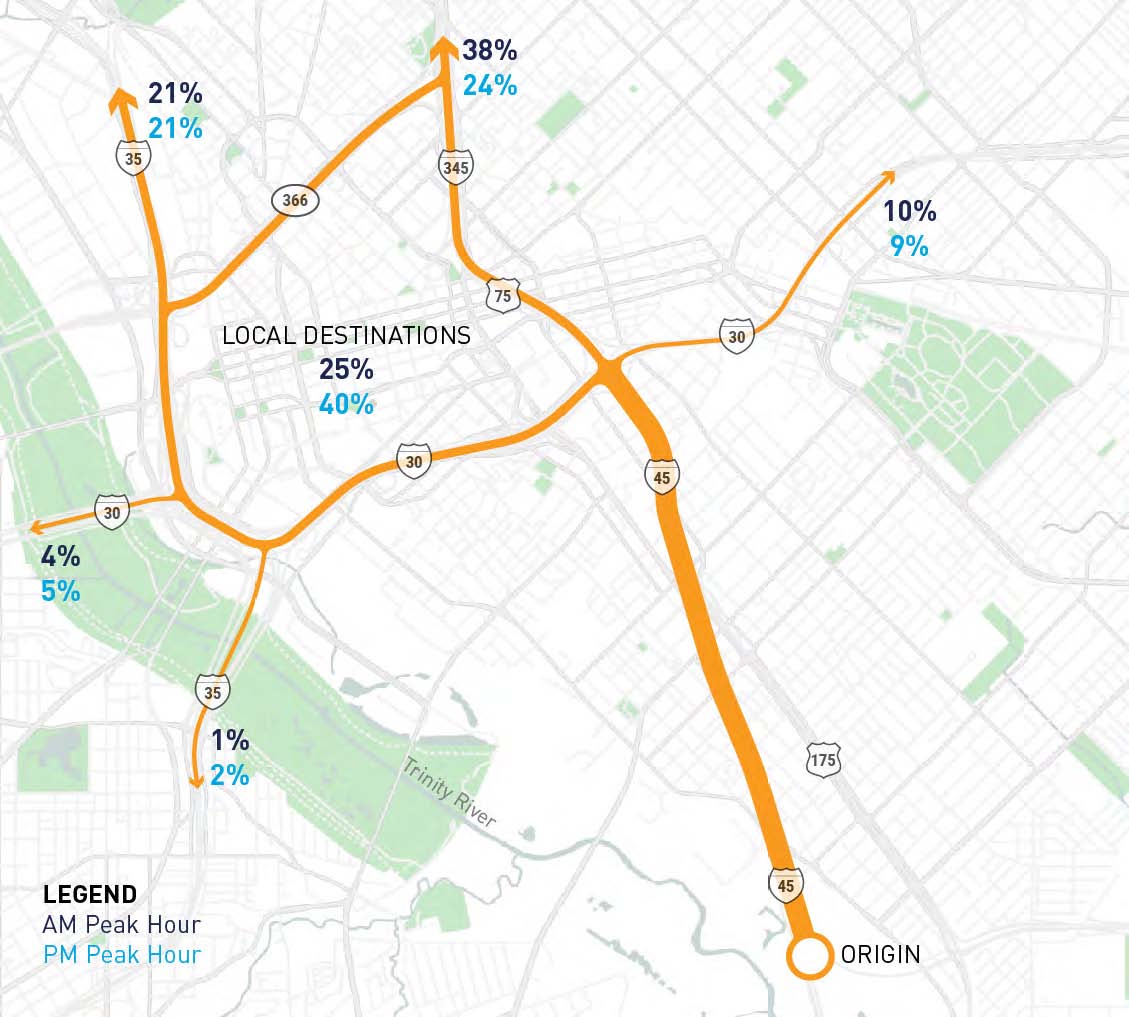

So how would removing I-345 affect traffic? While admitting that “there are no tools to forecast the traffic impacts of removing a highway,” the Framework Plan analyzes traffic impact by analyzing historical traffic data for I-345. It then compares it with traffic data for surface streets. It arrives at two fascinating observations about I-345’s peak capacity and total traffic volume on the highway.

According to traffic counts, I-345 can move a peak of 2,250 vehicles per lane per hour through downtown. This, of course, doesn’t mean that 2,250 cars are screaming past downtown in every lane 24 hours a day; that is the maximum capacity number used by traffic engineers. But what the Framework Plan discovered is that I-345 typically carries closer to 2,000 cars per lane per hour during peak morning and afternoon rush hours.

And here is where things get interesting: by comparing total capacity with the speed at which the traffic flows, the study found that I-345 can move the most cars when traffic is flowing at around 40 mph. Any faster, and that means there are fewer cars on the road, so less capacity. Any slower, and there is congestion, which means the highway is carrying more cars at slower speeds, meaning it moves fewer cars per hour.

Think about that for a minute. I-345 is most efficient when it is moving cars at a speed that is hardly any faster than how fast you can travel on a surface street. Keep that data point in your head, and let’s jump into the second fascinating aspect of this mobility analysis.

According to this new study, I-345’s eight highway lanes currently move about 18,000 180,000 vehicles per day and around 18,000 vehicles per hour. (Ed Note: a previous version of this story confused the per-day and per-hour vehicle capacity numbers in the report). If the highway were removed, the study argues that around 1,800 vehicles per hour would “evaporate,” meaning they are headed to destinations that don’t necessarily require I-345 to reach. In the absence of the highway, they would simply take another route. So, think of that total number of vehicles that rely on I-345 as something closer to 16,200 per hour.

The Framework Plan crunched the numbers on the current capacity of surface streets and found that 2.5 arterial streets could carry about the same traffic as one I-345 highway lane. The plan than maps out six existing streets that, taken together, could provide traffic capacity for some 17,000 vehicles per day hour. In other words, the report demonstrates how the existing street grid could handle I-345’s existing capacity. And since we also know that I-345 moves traffic most efficiently when vehicles are moving at 40 mph, the report argues there is no substantial loss of mobility when comparing I-345 with a reconstituted street grid.

That analysis helps show how, in some of the case studies included in the Framework Plan, the removal of a major inner-city urban highway – like the Embarcadero in San Francisco – did not impact overall mobility. Highways in urban centers are no more efficient than surface streets at moving traffic.

Highway Removal as a Silver Bullet

We should be wary of silver bullet fixes, particularly in areas as complex and multi-faceted as urban development. But the proposed removal of I-345 – if executed correctly – does have the potential to positively impact a wide variety of Dallas’ endemic urban problems. The new report identifies several of them:

Creating jobs: the new study estimates removing I-345 could lead to the creation of 39,000 new jobs and housing for 11,519 residents, which is higher than previous estimates.

Breaking a cycle of unsustainable infrastructure investment: If highways don’t alleviate congestion, as this study suggests, this means that Texas’ highway-centric transportation strategy is both extremely expensive and fundamentally unsustainable. According to the new report, 40 percent of Texas’ transportation budget ($8.6 billion) goes to maintaining the current system, and 30 percent of the budget is allocated for building new highways.

Hitting climate goals: This new study treats environmental justice as a key reason to remove the highway. The report recounts the history of how the construction of Dallas’ urban freeways destroyed and displaced many Black communities, while helping to entrench a cycle of disinvestment in many of those places. “While I-345 currently gives residents vehicular access between their neighborhood and services/jobs away from the neighborhood, it also disrupts the urban fabric and exposes nearby residents to air pollution,” the report states.

Currently, single-occupant vehicle trips account for 88 percent of Dallas’ overall percentage of greenhouse gas emissions. The city’s Climate Action Plan wants to reduce that to 62 percent by 2050. Removing highways to create more walkable communities is an essential component of meeting the climate plan’s benchmarks.

Creating new urban districts: Another improvement on CityMAP is the Framework Plan’s neighborhood vision plans, which show the potential for development after I-345 is removed. The renderings help drive home how much land the elevated highway impacts, and the scale of opportunity that exists once it is removed. This is not only significant for the specific neighborhoods impacted by the highway removal, but the city as a whole. As the report notes, most of Dallas’ recent economic growth has occurred in more dense and walkable urban places. But only 38 areas in all of North Texas can be considered walkable and urban places, which accounts for only around 0.1 percent of the entire region’s land area.

That’s a problem. Because walkable urban neighborhoods are in such short supply, they are extremely expensive places to live. That creates economic pressures on the real estate market that helps perpetuate cycles of gentrification and displacement. The only way to break these cycles is to build more walkable communities, to create additional supply to meet demand. Removing I-345 presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rapidly increase the number of walkable, self-sustaining urban communities in the city. If developed properly, this could bring both jobs and affordable housing to the doorstep of neighborhoods that need it most.

The report lacks a more detailed analysis of land use policies that could ensure that new developments include affordable housing, services that meet the needs of surrounding communities, and job opportunities for southern Dallas neighborhoods. That will require complicated policy tools that are worthy of their own extensive study. That needs to be done. In addition to fears of how a removal of I-345 will affect mobility, there are understandable concerns that new development will follow in the typical Dallas, Uptown-esque fashion, creating a shiny, pricy new neighborhood serving only those who can afford it.

What’s Next?

As I mentioned up top, the Coalition for a New Dallas will present this plan to the public tomorrow. The three major downtown Dallas transportation projects—D2, Interstate 30’s redesign, and I-345—are all moving into advanced stages of planning. This report comes at a time when public officials are looking to tie those three projects together in ways that could determine their shape and scope and their impact on the neighborhoods they exist within. The pending TxDOT I-345 traffic study will also lay out some assumptions that could shape the public debate around the future of the removal project. This report adds context to that conversation, offering a weighty counterpoint should TxDOT argue that removing the road will trigger a transportation catastrophe.

But more than fodder for highway removal champions, this report continues a new model for long-range planning that CityMAP initiated. CityMAP gave public officials a clear set of shared values and objectives that have helped guide the planning process around I-345 and the other highways that crisscross our city. It is one of the things that has helped Dallas avoid the kind of blow-up that has consumed TxDOT’s Interstate 45 expansion project in Houston, which has devolved into a political and legal nightmare. This Framework Plan – a kind of CityMAP II – should provide similar guidance as those negotiations move into the next phase.

It is significant, then, that this new report is not merely the product of a single design consultant, but the product of a wide range of community organizations and partners. In that sense, it also offers a model for the kind of community engagement that should take place as I-345—and the other major downtown transportation projects—move forward.